This post contains part IX of my senior capstone paper, Speed Limits: The Formation, Dissemination, and Dissolution of the Counterculture in American Literature 1951-1972. Click here to view a full list of works cited. Click here to view all sections of the paper.

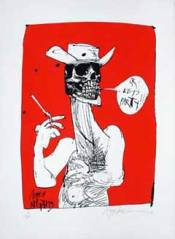

Ralph Steadman’s take on Thompson

Image from Examiner.com

Thompson’s writing exposes the inherent hypocrisies of the counterculture movement and helps explain why, only four years after the hope and rage of 1968, the movement had become a washed-up mockery of itself—and inadvertently paved the way for a conservative revolution. Suri points out that “the counterculture’s mainstream roots raised expectations for extensive political reform, but those expectations were ultimately a victim of the coercive leverage exerted by the figures who dominated the mainstream […] Rapid political change required something much more akin to social revolution than what the international counterculture could offer” (Suri 53). The leaders of the counterculture ended up as corrupt and manipulative as the mainstream political figures they railed against—instead of coercing followers into racist status-quos and unnecessary war, they instead lead them into extreme indulgence and a near-deadly narcissism.

Thompson expresses disappointment with the so-called leaders of the counterculture movement, especially the great Chief himself, Ken Kesey: “Tune in, freak out, get beaten. It’s all in Kesey’s Bible. . . . The Far Side of Reality” (Thompson 89). Throughout Fear and Loathing Thompson provides an echo to the Pranksters’ final refrain—“WE BLEW IT!”—and adds to the mix his own interpretation of the consequences. After the worldwide civil unrest of 1968, government leaders “rebuilt their authority around commitments to restore rationality, reasonableness, and domestic peace” (Suri 63). Needless to say, calls for “law and order” were immensely appealing to the “silent majority” of Nixon voters who lived in dread of the violent chaos that the countercultural movement had come to represent. Thompson writes from a place of disillusionment as he grapples with the fact that the movement he once believed in has been left flailing and leaderless while a conservative climate of fear and loathing had taken hold of America. Continue reading